Codex paper

You have to go back to the ancient civilisations of pre-Columbian America, the Mayans and the Aztecs to appreciate all the historic richness of paper made by hand in Mexico.

Using the bark of the ficus - huge wild fig trees growing in the Yucatan - the Mayans produced magnificent papers in the 10th century. They made the pulp from the white and tender part of the tree between the dark bark and the core. Their technique was to spread the ficus bark and hammer it using a wooden mallet to obtain the something on which they wrote superb codex. These fascinating documents were generally allegories on life and death.

For their part, the Aztecs made several improvements to the recipe to develop the famous Amatl paper also known as Amate. The Aztecs cut off branches of guava, a huge fibrous plant from which they extracted textile fibres and which they then soaked in the river to make them more malleable and stripped them of their bark. They then beat them with a stone, flattening and smoothing them to make Amate paper.

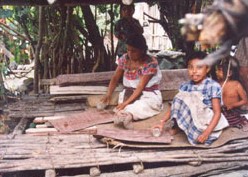

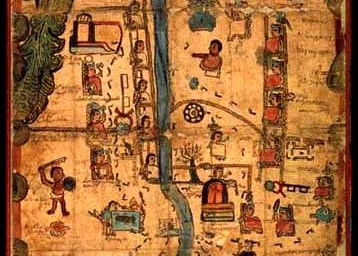

The Amate paper produced in large quantities by the Aztecs and their Zapotec and Mixtec tributaries until the Spanish Conquests (1519 -1546) was rapidly supplanted by papers from Europe. Nevertheless the Otomis from San Pablito in the state of Puebla in the centre of Mexico continued to make it until modern times according to ancestral recipes. Softened by heating over a small flame for several hours in water containing cinders, fibres from various kinds of ficus are disposed in crossed strips on planks of wood to be hit manually by stones. When the fibres are amalgamated into a homogeneous mass, the planks are placed in the sun to dry the paper which can subsequently be prepared to be written upon. Among the rare documents dating from the 16th century written on amate paper which still survive, we find books folded in an accordion shape or sewn in Codex, and especially "mappas". These are made up of several 20 cm by 40cm sheets of paper and bound with glue. They recount events happening in the Tlapa region, before and after the Spanish conquests

The sound of people pounding pulp into paper can be heard echoing off the hills around the town of San Pablito in the Sierra Norte in Puebla. The color and grain of the paper depends on the bark used to make it. The typical coffee color comes from the Jonote tree (ficus family), white from the Xalama Limón, and the silvery beige color from the Mora (mulberry family), to name just a few varieties. Years of practice let the Otomí artisans make different sizes and thicknesses - from poster-board to crepe-paper weight.

The practice of making Amate paper has been kept alive due to its important role in Otomí religious ceremonies. The cut-out figures represent different good and bad spirits and are used in offering ceremonies, for example for a good corn crop, as well as for curing sick people. The figure at the right is known as the Lord of the Mountain. Each family has to know how to make the paper in order to give it to the shaman so that he can cut out the figures for each ceremony.

Artists from San Pablito have gone on to make elaborate designs with these figures, usually around sun images. They are made in a thin, dark colored sheet of paper, which is then pounded into a white sheet of Amate paper while the white one is still wet. The artist does not draw the design on the paper, but cuts directly from their creative vision and memory. This art is known as "Amate Picado". A simple design with a pineapple spirit is shown hereunder.