Origin of the celebrations

1. The story of St. Valentine

How long is it since Cupid sent his arrow to your heart?

50 years, 20 years, 10 years, one year? However long it is, do not forget that the celebration of lovers has existed for many, many years. Of course, it has evolved, but St Valentine is always a unique occasion to declare our love to the one who has won our heart, as well as to our friends and our parents. Although today, St Valentine is synonymous with joy and love it must not be forgotten that poor St Valentine gave his life to defend the rights of people who love each other.

Valentinus was a Christian priest on whom the Roman Emperor Claudius the second exercised his wrath. He performed secret marriage ceremonies for soldiers. But the Emperor had forbidden these marriages because he thought they were not compatible with the profession of soldier. Claudius ended his activities in an extremely bloodthirsty way: Valentine was thrown into prison, then beheaded on the February 14th (sometime between 268 and 273 AD). While he was waiting for his sentence to be carried out he met his jailer's blind daughter. A friendship developed between them and Valentine restored her sight. Just before he was martyred, he offered the young girl leaves in the shape of a heart with a message "from your Valentine". Later, Valentine was canonised in memory of his sacrifice in the name of love.

Two centuries after his death, European Christianity included other pagan rites such as the Festival of Lupercus (synonymous with exuberant rejoicing) which took place on the February 15th as a souvenir of the Roman period. This was the perfect occasion to celebrate fertility. It was recognised by the Catholic Church thanks to the intercession of the Pope who was keen on commemorating it. It was also associated with St Valentine who was called the protector of loving couples. It was only in 1496 that St Valentine officially became the patron saint of lovers on the orders of Pope Alexander the VI.

Still today, lovers take the opportunity of St Valentine's Day to exchange cards and give gifts such as flowers and chocolates, which are always synonymous with passion as a token of their love.

2. Easter around the world

Easter was originally a pagan festival, or a festival celebrated by non-believers. To start with Easter was a spring festival in honour of light and springtime: Eastre. Easter falls on the first Sunday following the first full moon in spring. The festival was held to celebrate the renewal of life. This is why symbols of fertility, such as rabbits and eggs, are associated with Easter time. Hence Easter was not originally a religious festival. Later on the festival took on a specific meaning for believers, a meaning that was an extension of the original meaning. The Christian meaning of Easter is a celebration of the resurrection of Jesus Christ. The Easter festival is celebrated in almost every country in the world but the festivities differ from one country to another.

The people of the United Kingdom celebrate Easter, while the Germans celebrate Ostern. These names refer to Austro, the German goddess of spring. The triumph of light and life is celebrated with the lighting of bonfires during these festivals. Azymous bread and eggs are also an important feature of these different rituals.

Where do Easter eggs come from?

It all began in Persia and Ancient Egypt. Friends and family members would offer each other decorated eggs at the vernal equinox, which for them marked the beginning of a new year. The egg was regarded as a genuine symbol of fertility, because people thought it was a miracle for a living creature to be able to emerge from such an object. The egg had a much less hormonal meaning for Oriental Christians. For them it represented the tomb Jesus escaped from. They, too, enjoyed colouring their eggs and red was the colour of choice. It was supposed to symbolise the blood of Christ. Consequently, all believers could participate in Christ's resurrection. The practice of hiding eggs is said to be a universal custom.

Easter is inextricably linked with eggs. To discover how the egg became a key item of this festival we have to travel far back through the mists of time. Our Germanic ancestors celebrated their spring festivals at this time: the end of winter, the start of the summer months.

Consequently, it is only to be expected that they should venerate their spirits by making offerings to the goddess of fertility: Frigga. She was represented by the shape of a bird: the one who gave birth to an egg. In the wake of these offerings, the people would gather together for generous meals comprising, eggs, loaves of bread and biscuits cooked with eggs.

The origin of all forms of life

The egg has long symbolised the origin of all forms of life, so it is not surprising that the egg should be regarded as a symbol of fertility in almost all countries, while being associated with the spring festival.

The egg forms the background to a new world in innumerable ancient histories. In India it was even believed that the sky and the Earth emerged from an eggshell. A Japanese story about creation relates that the sky and the Earth were not yet separate from each other in the very beginning. The yolk and the white of an egg is evoked to illustrate this theme. According to this myth, the sky is derived from the light (white) and the Earth from the dark part (yolk) of the egg.

Eggs may have originally been a pagan symbol, having no connection at all with Christianity, but they ended up being carefully paralleled in Christian doctrine in the 4th century: the egg was regarded as a white tomb from which life emerged. By the 12th century, the "Benedictio ovorum" had been introduced, authorising the use of eggs on the holy days of Easter.

Magical effect

The Scottish Presbyterians tended to look askance at eggs, regarding them as a symbol of papal adoration. In other places, eggs were looked upon as beneficial delicacies: they were offered in churches after people had spent weeks in the strict observance of Lent. This ecclesiastic recognition served to accentuate their magical power. Eggs soon became accepted as a charm that had a special effect.

Innumerable Easter customs began to appear: collecting eggs, breaking them, hunting for them and eating them in large quantities in the form of loaves of bread and pastries, biscuits and cakes (particularly in the United States and England), marzipan, nougat, sugar, and, of course, chocolate. The remnants of an ancient votive meal are concealed in azymous bread, which also features traces of the Jewish azymous bread.

The bakers and confectioners of that time observed ancient customs. They baked azymous bread, egg-based pastries, pasties and egg biscuits. Chocolate makers prepared their chocolate eggs and confectioners their marzipan and nougat in various shapes and sizes. They produced enormous quantities of these items decorated in thousands of different ways.

The Easter hare

The Netherlands is the odd one out on this score. Easter bunnies are found all over the world, while the Dutch are the only people to use a hare. Still, they are from the same family, are they not?

When rabbits used to appear and disappear without any explanation way back in time, people would see an obvious resemblance between the appearances Christ made after his resurrection. The first historical references to the Easter bunny can be traced back to Germany. Documents from the 16th century refer to a rabbit laying red eggs on Good Friday and multicoloured eggs the evening prior to the first day of Easter.

Other symbols

The Easter bunny may be the unchallenged king of Easter symbols, but other charming creatures also come into the picture. The chick, for example, has been around as long as the egg. The lamb's appearance at around Easter time has been a popular event for centuries now. The lamb + chick + bunny combinations are especially popular. The butterfly is less well-known. The Christians saw a striking parallel between the caterpillar's transformation into a butterfly and Christ's resurrection. The lily also formed part of the Easter festival. This delicate, pure white flower is particularly prominent in the works of art of the ancient Christians.

Easter and culinary delights

As you may have read, lamb has not always been the first choice. Fortunately for this creature, azymous bread, biscuits and cakes have long been the favourite food items. From the edge of the New World to the depths of Russia, azymous (or unleavened) bread is by far the most popular one. The Russians eat "paska ", the Germans "osterstollen" and the Poles "baba wielancona".

Easter celebrations

The ancient Christians looked upon Easter as a time for humour. All week long people would be cracking jokes, larking about and roasting large numbers of lambs. There would be singing and dancing late into the night. The people were celebrating the fact that Christ had taken the Devil and Evil down a peg or two.

On Easter Monday, the men would wake the women up with a few drops of perfumed water along with the words "may you never wither". The next day the women would wake the men up with perfumed water. The subtle difference here was that the women were allowed to pour the contents of a bucket over their husbands.

The Easter celebrations vary enormously nowadays. They differ quite a lot from one country to another and very often from one religion to another. The way the members of the Eastern Orthodox Church celebrate the first day of Easter is even more outlandish than their forefathers. The Lutheran Churches in Sweden and Norway, conversely, have had to adapt to some of the people's contemporary customs.

Most of people go on holiday to the mountains at Easter. Nothing if not innovative, the Lutheran church has built one or two mountain churches on the spot.

Why do the bells bring eggs?

The idea that the bells bring the eggs is linked to the fact that the bells ring for the last time before Easter on Maundy Thursday. Children are told that the bells have left for Rome and will be returning on Easter morning with their eggs.

Why does Easter fall on a different day every year?

Easter Sunday is a bit different every year: it can fall as early as 22 March and as late as 25 April. The reason for this is quite straightforward: the Christians calculated the date according to the lunar year rather than the solar one now used for the calendar. The reference point is not the position of the sun but the rising and setting of the full moon. Easter should always fall on the first Sunday following the first full moon, the Bishops of the Catholic Church decided during the Nicaea Council in 325. The church leaders agreed that Easter should be on a Sunday, to make a distinction between the Christian and Jewish religions. During the second Vatican Council, in the 1960s, church officials mooted the idea of having a more set date for Easter, one that was closer to the historical date of Jesus' death, around 10 April. Easter Sunday would then have been celebrated after the second Saturday in the month of April. However, this idea never got off the drawing board: the Catholics, Protestants and Orthodoxes failed to agree on a new rule.

What are Christians actually celebrating at Easter?

Christians regard Easter as the most important day of the year. The birth of Christ is celebrated during the Christmas festivities, but Easter, the day when the man Christians believe is the son of God was resurrected, is a much older festival. Christmas was not originally celebrated unlike Easter. In the final analysis, Easter Sunday marks the conclusion of an entire week when Jesus was betrayed and sentenced to death after the last supper with his disciples. He died on the Cross on Saturday and on Sunday the rock in front of his tomb was discovered to have rolled away and Christ's body had disappeared: Jesus was not dead, but risen from the dead.

He appeared to his disciples a few more times before ascending to Heaven 40 days later, during the Ascension.

Why do the French call Easter "Pâques", the English" Easter" and the Germans " Östern"?

The name "Pâques "originated with the Jewish Pesach festival, when a lamb is sacrificed to celebrate the Jewish people's deliverance from Egyptian bondage. Jesus and his disciples were originally Jewish and Christ rose from the dead after Pesach. The Christians regard Jesus as the Easter lamb which was sacrificed to allow the deliverance.

The Muslim and Jewish practice of slaughtering a lamb every Easter used to be a Christian custom, too, but this practice gradually died out: Jesus sacrificed himself so why carry on slaughtering a lamb? The tradition is still maintained by certain groups of Catholics, however.

The English and German origins of the word are more complicated. Ostara, the Germanic goddess of fertility and spring, forms the background to the name. A historical investigation showed that Ostara was not in fact venerated by the Germanic people and was not mentioned in the literature until the 8th century. The other explanations are linguistic in nature. Urständ, the high German word for "resurrection", may be the basis for "Easter" but the word may also be derived from a mistranslation of the Latin phrase "hebdomenica in albis", " the week in white robes" following Easter Sunday. It was then assumed that "albis" mean "aube" (dawn) and not (white). The high Germany word for "aube" is "eostarun", towards the east where the sun rises. The English variation was then "Easter ", "Östern" in German.

The Easter bunny

How can a rabbit or hare lay eggs?

The tradition of looking for Eastern eggs originates with an old story about fertility: The German goddess Freya had a pet: a hare, which rather than game had belonged to the poultry family in a former life. This is why the hare could lay eggs. At the start of the new year (springtime), Freya would let her hare hide her eggs in the fields so the peasants could be sure of having a bumper harvest.

Egg is synonymous with new life

However, there are lots more stories involving the egg and spring. The egg has taken on a symbolic meaning in almost all cultures over the centuries.

One example is the mythological story of Kronos, the son of the sky god and the earth goddess: Uranos and Gaia. They are said to have created an egg from which emerged the many-headed god Phanes, whereupon the Earth was formed. The exodus from Egypt is celebrated during the Jewish Easter festival. The first two evenings of the eight-day festival are called "seider". A special meal, the "seider" is served then as well as the "matses" (azymous bread), spices, parsley, horseradish and boiled eggs.

In this case the boiled egg is also a sign of mourning for the former temple of King Solomon. It is a symbol for an entire meal in commemoration of the second festive offering formerly held in the temple.

Tip:

The older an egg is the more it floats. In order to check if an egg is fresh place it in a basin full of water. A fresh egg stays on the bottom, whereas one that is three or four weeks old will stand up on the bottom, a six-week old egg will remain "suspended" in the water but if the egg floats, it definitely should not be eaten.

3. St. Martin - Martin of Tours

The life of St. Martin

Martin was born in Sabaria, Hungary, in the year 316, now called Szombathely (Pannonia) in the eastern part of the country. His father was a magistrate in the service of the Roman army. The family relocated to Pavia, Italy, where he spent most of his childhood. Legend has it that he joined the church as a catechumen (or a candidate for baptism), despite his parents' resistance (legend most likely makes a connection here between the evangelical story of the young Jesus aged 12).

He enlisted in the Roman army when he was 15 under Emperors Constantine and Julian and joined the cavalry in Gaul (France). According to history, it was during this time that he met a scantily dressed beggar at the gates to the city of Amiens. The beggar asked him for alms according to Christ's will. As he had nothing else with him except his weapon, Martin offered part of his military cloak, which he cut in two with his sword. At that time, half of a soldier's clothes belonged to the emperor and the other half was the soldier's personal property.

Christ then appeared to him in a dream wearing the half-cloak. "What you did for the weakest one of my brothers, you did for me". This dream persuaded him that he should become a Christian and be baptised. The ceremony was conducted by the Bishop Hilary of Poitiers. During his time in the army he was increasingly tormented by an inner struggle: whether to devote himself to the service of the Roman emperor as a soldier or concentrate on his Christian calling. In the end, he decided to leave the army.

He was baptised at the age of 18 (other sources say 22) and was admitted into the ecclesiastical body of the church. He completed his first work as a priest in the region where his parents lived, in Lombardy, where he proclaimed the Christian faith. He then clashed with the Arians, a Christian movement that maintained the human dimension of Jesus of Nazareth, refuting the divine origin of Christ. Arianism had a large number of followers. Martine refused to renounce his beliefs, so was mistreated on the orders of the Arian bishop of Milan. He then went into hiding as a hermit on the island of Gallinaria (now called Isola d'Albenga) on the Italian Riviera.

He was able to return to France in 361 and re-establish contact with Hilary of Poitiers. He also became a hermit there, living in remote region and devoting his life to God. As a result of attracting a great many followers he was able to build the first monastery on French soil, in 361. When St. Lidorius, the bishop of Tours, a city in the western part of France, died in 371 or 372, the Christians and the priest living there asked Martin if he would like to become their bishop. However, he wanted to remain a hermit. Legend has it that Martin was drawn to the city as a result of a trick. Once he reached Tours, he was unable to renounce the episcopate. The people elected Martin as bishop of Tours in 371. He continued to live the life of a monk. He founded a monastery in Tours in 375 and worked with his followers in spreading the Christian religion in France.

He continued to live his monastic life as a bishop and acted as a major proclaimer of the faith. He founded several monasteries, including the one in Marmoutier. He had the pagan sanctuaries destroyed, while being tireless in his efforts to denounce the heresies of the time.

He was already regarded as a saint during his lifetime, while several miracles were attributed to him. He died in Candes at the age of 81 during a mission on 8 November 397. He was buried in Tours on 11 November, his current feast day. He may not have died a martyr like so many of his predecessors, but he was immediately regarded as sacred by all of the people. Several miracles occurred around his grave and one century later king Clovis named him as the patron saint of France. Thousands of churches in France have been dedicated to him, including the famous St. Martin Basilica in Tours. His reputation also extends northwards, particularly in Flanders and the Netherlands, along with a part of Germany, which used to belong to France. Several St. Martin parishes are found in Flanders, spread throughout the region, mainly in the villages, of course, whose names refer to St. Martin. Examples are Sint-Martens-Bodegem, Sint-Martens-Latem, Sint-Martens-Leerne, Sint-Martens-Lennik, and Sint-Martens-Voeren.

The word "chapel" is also derived from a relic of St. Martin's.

A cape is "cappa" in Latin and the diminutive of this word (it was in fact only part of the cape) is called "cappella" in Middle Latin. This term gradually started to be used to refer to the tent where the cape was kept. By the 7th century, any small house of prayer that was not a parish church was called a "capella".

The word now appears in all contemporary languages : "kapel" (NL), "Kapelle " (D), "chapel" (E), "cappella" (I), "capilla" (ES), "chapelle" (FR).

Take the French word for Aken, the residence of emperor Charlemagne : Aix-la-"Chapelle ". In the this case, "chapelle" no longer means a tiny church but the dome dedicated to Mary and not Martin, as we might mistakenly deduce from the origin of the word "chapelle ".

By the 16th century, royal personages were accustomed to inviting singers and musicians to their castles during religious festivities: they were also an "orchestre" ("kappel" in Dutch). Musicians subsequently passed the word onto laypeople, an example is the French "chef d'orchestre" (conductor or " kapelmeester " in Dutch).

4. The origin of Halloween.

Halloween began as an ancient Celtic ceremony called Sawhain, held on the evening of 1 November.

The Halloween festival appeared between 500 and 1000 BC and is supposed to have been the Celtic "New Year". These people regarded 1 November as the Sawhain (pronounced: Saw-En), meaning "the end of summer"

This day was a special one marking the end of the previous year and the start of the new one. Dead people were supposed to return to earth. Some people believe the spirits wanted to inhabit a body, which is why fires were extinguished inside homes and fires were lit outside to chase away the spirits.

What form the celebrations took during the festivities is still shrouded in mystery but one thing is certain: they were held to celebrate the end of the fertile year and the start of winter. Once the cereals and fruit had been harvested, prior to the onset of winter, any surplus animals were slaughtered. This is why the month of November was called blodmonath in old Anglo-Saxon literature or slachmaent in Middle Dutch. The final fruit had to be picked before the Sawhain festival, as anything hanging on the bushes after that date was intended for the spirits. Two bonfires were lit during the festivities. This period was devoted to the commemoration of the dead. This formed part of the worship of the Celtic ancestors and may therefore have been less restrained than contemporary commemorations.

The Celts believed that the dead had gone onto "another world", sometimes an island in the middle of the sea, sometimes an "inverted" subterranean world. During the Sawhain festival, the separation between the two worlds was very slight and the spirits entered were said to enter our world at exceptional times to warm themselves at their descendents' fires. These pagan festivals in November continued for a long time in this part of the world, only to be absorbed by the Christian religion in Europe. The Christians also organised their own commemorations for gods. They did not evoke spirits but saints. However, as there were so many saints it was impossible to earmark a special day for each one. This is why the day of commemoration was shared by the community of saints after the 7th century.

The day was celebrated everywhere in Europe in springtime but not necessarily on the same date. All Saint's Day was moved to November in the 9th century under the influence of the Irish church, anxious to abolish pagan customs. The Day of the Dead suffered the same fate. This was a service where prayers were offered up in honour of the souls of the dead. These prayers were highly popular in the French abbey monasteries and went from strength to strength to become a separate feast day.

This festival also took place in the spring but was moved to November for the same reason. The evening before All Saints' Day was called All Hallows Eve, which evolved into Halloween. The pagan and Christian commemorations for the dead were merged to become a single festival, whose popular components still often refer to pagan customs, where the religious dimension has become Christian.

Halloween became hugely popular in the United States owing to the large wave of immigration in the wave of the Irish potato famine, according the Lauvrijs. Millions of Irish people sought refuge in the United States in the 19th century. And it was these Irish emigrants no less that introduced the Halloween festival into North America.

Halloween is now celebrated on 31 October in EU, while the special offers start early in October and last until the first week of November.

The items of food associated with this special day were: carrots, apples, special types of bread... and of course sweets for the children!

This festival has become a major commercial event in the United States and is becoming increasingly popular in other parts of the world.

Why a pumpkin?

The Halloween pumpkin frequently used today hails from the United States. The various light spirits were celebrated in Europe with hollowed out beets and turnips. Children would cut faces into these vegetables and parade them proudly through the village in the evening. Irish immigrants in the United States replaced the European turnips with pumpkins, as these were much more common. The name of the hollowed out beet is derived from Anglo-Saxon folklore: "Jack-o'-lantern".

5. St. Nicholas

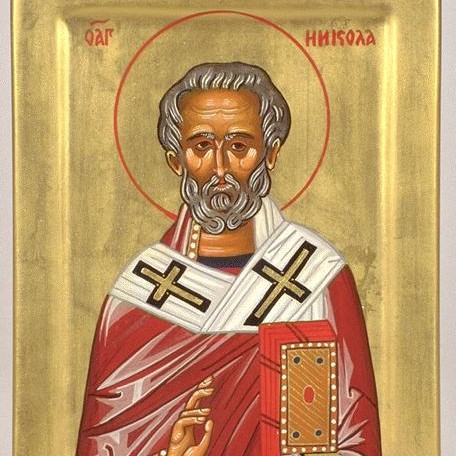

1. Who is St. Nicholas?

The Vatican cannot tell us.

The are so many versions of the story of St. Nicholas, while the true history of the man's life has tended to become blurred in the mists of time, that even the Catholic Church has started to raise question's about the Saint's true status. During a review of the list of saints, in 1959, the Vatican agreed to remove 200 names, including that of St. Nicholas'. The Vatican claimed that two pagan legends had been merged but the officials in Rome were wary of treating this as an open and shut case. Pope Paulus V announced in 1970 that: "He may be venerated but there is no need to do so".

The character of St. Nicholas draws its inspiration from Nicholas of Myra, also known as Nicholas of Bari. He was born in Patara, a Lycian city, in the south-western part of Asia Minor (a region now known as the Asian region of Turkey) between 250 and 270 AD.

He died on 6 December, in 345 or 352, in the port city of Mrya, in Asia Minor.

Legends abound about his life and deeds. It is said that on the day he was born, he stood up in his bath. As he grew older he would shun merrymaking in favour of attending church.

St. Nicholas went on a pilgrimage to Egypt and Palestine. On his return, his uncle, the bishop of Myra, died. A tiny voice urged the assembled bishops to elect the first person to enter the church as the successor to the deceased bishop. And so it was that Nicholas was ordained as bishop of Myra.

His Christian faith initially caused him a lot of suffering because of the reigning emperor, Diocletian, who persecuted Christians ruthlessly.

Nicholas was arrested and flung into prison before being made to live in exile.

Emperor Constantine announced in 313 the toleration of Christianity. He is also said to have been present during the Council of Nicaea but doubt has been cast on this claim because his name is not mentioned in the old list of bishops who attended the event.

St. Nicholas is said to have died on 6 December 343, a victim of persecutions during the time of the Roman Empire. This is why some countries celebrate the feast of St. Nicholas on 6 December. He was buried in Myra but some Italian merchants stole his relics in 1078 and carried them to Bari.

The traditional legends surrounding St. Nicholas were collected and written down for the first time by Metaphrastes in Greece during the 10th century.

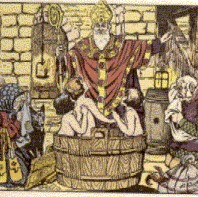

According to legend, St. Nicholas succeeded in bringing three children back to life after a butcher, from whom they had sought refuge, waited until they were fast asleep, then cut them into tiny pieces before placing them in a salting tub.

Seven years later, St. Nicholas travelling along the same route, asked the butcher to serve him the seven-year-old salted dish. When the terrified butcher had run away, St. Nicholas restored the children to life.

Why is he famous as the protector of marriageable maidens (throwing sweets and gold balls)?

St.Nicholas, possibly on his way in his city again, threw money into the house of a family whose daughters had little prospect of getting married owing to their straitened circumstances. The maidens were saved from prostitution thanks to the Saint because they now had a dowry with which to find a decent husband. The custom of throwing sweets (ginger nuts, confectionary and golden chocolate money) originates with this story. That is why three gold balls are one of the symbols for St. Nicholas. Another reference is to the "good holy man", from "goet-hylik man", which means "good marital man", the man who ensures a good marriage.

A teacher gave St. Nicholas a face

A story truly becomes popular when the characters are given a face. Of all the illustrations that are available of St. Nicholas, the ones that have had the biggest impact on the feast of St. Nicholas in its present form are those appearing in Jan Schenkman's books. In1845 this teacher living in Amsterdam wrote the first book about St. Nicholas, featuring the saint and his companion Black Peter.

Comprising illustrations with 12-line verses, the book was never out of print for over 100 years. An amazing best seller! Schenkman invented the story of St. Nicholas and his horse going from one rooftop to another, arriving on a steamship, which was a modern system of transport at the time. Where did this ship hail from? From Spain, according to Schenkman. And why Spain exactly? Because Bari (Italy), where the tomb of "one" St. Nicholas was located, belonged to Spain at one time. However, the true history of St. Nicholas has long been overshadowed by imaginative tales and legends, so it is quite possible Schenkman made everything up.

2. Black Peter

St. Nicholas is accompanied by a rough character with a dark face carrying a cane.

He is known as " Père Fouettard " in some parts of France and Belgium's Wallonia and "Zwarte Piet" in Flanders and the Netherlands. He is tasked with caning children who have behaved badly during the year.

This character only came to fame in the 16th century.

Who is he ?

One legend say Black Peter was born in Metz in 1552, during Charles V's siege of the city.

The inhabitations walked around the streets with an effigy of the emperor before setting it on fire.

Consequently, some people claim Black Peter represents Charles V.

The following is another explanation.

Peter presumably first of all enters folklore in the Lowlands in the early nineteenth century. Up until then St.Nicholas had operated alone or was accompanied by the devil. A devil and a Moor were considered to be more or less the same thing by Europeans at that time. Owing to the now popular tradition that the Saint originated from the former Moorish Spain, the servant was transformed into a Moor. In keeping with colonial tradition, up until well into the second half of the twentieth century Black Peter was a bit of a dim helper who spoke gibberish As a result of immigration from the former colonies, Europeans became more familiar with Africans, whereupon Black Peter developed into the respectable assistant of an often absent-minded Santa Clause. Black Peter became less dim, but this does not mean the Black Peter tradition is not open to challenge. Many people still take offence at the racist side of the tradition. For many people, Black Peter is a merry children's friend who is black because of chimney soot. This still does not explain how Black Peter was assigned the attributes of crude stereotypes, such as red lipstick and frizzy hair.

According to another theory, Black Peter was originally an Italian chimney sweep. Small Italian boys were used for a long time as chimney sweeps. They had to crawl though chimney flues as part of their duties, hence the soot from cleaning the chimney and the bag for collecting the swept-together soot.

3. How did St. Nicholas change into Father Christmas ?

In the wake of the Protestant reform in the 16th century, some European countries decided to ban the feast of St. Nicholas.

However, the Dutch retained this old Catholic custom, and Dutch children continued to receive a visit from Sinter Klaas (St. Nicholas) during the night of 6 December.

At the start of the 17th century, Dutch people emigrating to the United States founded a colony called "Nieuw Amsterdam" (in Dutch) and this became New York in 1664. Within a few decades the Dutch custom of celebrating St. Nicholas had spread all over the United States, where Sinter Klaas soon became Santa Claus.

The considerate benefactor, depicted as an old man sporting a white beard and wearing a long hooded coat or sometimes episcopal clothing, nonetheless continued to be a moralising character. He rewarded good children, while punishing ungrateful badly behaved ones.

In 1809, the writer Washington Irving spoke for the first time about St. Nicholas flying through the air for the traditional present-giving activities.

Then in 1821 an American pastor, Clement Clarke Moore, wrote a Christmas story for his children where a kindly figure appeared, Father Christmas, with his sleigh pulled by eight reindeers.

He made him chubby, jovial and smiling, replaced St. Nicholas' mitre with a hat, his cross with a stick of barley sugar and removed Black Peter from the scene. The donkey was replaced by eight spirited reindeers.

The American press was responsible for bringing the various present-giving characters all together in the same person.

The event that definitely did the most to merge these characters was the publication of Clement Clarke Moore's famous poem "A Visit from St. Nicholas". This poem was published for the first time in the New York Sentinel, on 23 December 1823. Reproduced by several major American newspapers in the coming years, the tale was then translated into several languages and spread throughout the globe.

In 1860, Thomas Nast, an illustrator and caricaturist working for the New York publication "Harper's Illustrated Weekly", drew Santa Claus with a red costume, trimmed with white fur and set off with a wide leather belt. For 30 years Nast produced hundreds of drawings to illustrate all the facets of the Santa Claus legend, who French speakers know as père Noël (Father Christmas).

In 1885, Nast decided the whereabouts of Father Christmas' official residence should be the North Pole: he drew two children looking at a map of the world, tracing his journey from the North Pole to the United States.

The following year, the American writer George P. Webster took up this idea explaining that his toy factory and "his house, during the long summer months, was hidden in the ice and snow of the North Pole".

6. Christmas

Christmas and its mysteries

Christmas is not only the celebration of joy and hope for Christians. For all men and women of good will in our Western world, the birth of Christ marks a capital date for History: the beginning of the Christian era, the chronological base of the events which have followed one another over twenty centuries.

However, certain specialists assert that the 4th century scholars failed to take everything into consideration when they established that the Child-God was born in year 753 of the foundation of Rome. They claim that it is simply a question of looking at the facts: today we know with certainty that Herod died in the spring of 750. When that monarch ordered the famous "massacre of the innocents", Jesus was indisputably already several months old. The obvious conclusion therefore is that Jesus must have been born at the latest at the end of the Roman year 749. Consequently, it would be logical to believe that our clocks are slow by a trifling matter of … four years.

Why 25 December?

It was only in the middle of the 4th century (yes that century again!) that Christmas became an official festival of the liturgical calendar. Previously, the Church had considered Christ's date of birth date to be 6 January, i.e. 18 April. For lack of precision, it finally opted for 25 December, that is to say the day after the winter solstice, the shortest day and longest night of the year. No other date could better symbolise the coming of a "God of Light", the conqueror of the darkness of sin, of a god who rose like the sun to illuminate the whole of the world with hope. Moreover, our current "Christmas Eve" parties are simply a relic of the Pagan Saturnalia, kinds of carnivals with large banquets that the ancient Romans dedicated, from 17 to 23 December, to their god Saturn.

Noel or Nativity?

The actual name of Christmas or Noel, to designate the Nativity Festival, seems clearly to have been used only five centuries after the event. Converted after his victory of Tolbiac in 490, King Clovis was baptised at Rheims by Saint Remi, with 3,000 warriors, precisely on 25 December. On that day the Frankish nation was born to Christian civilisation. The soldiers celebrated this memorable event with a vigorous cry of "Noel" which meant "dies natalis" or "day of birth".

Since then the name of Noel has always been associated with this famous date.

The nativity scene

If the reproduction of the small stable with its wooden or plastic characters and animals clearly appears to have been initiated by Saint Francis of Assisi, the great lover of animals, the tradition of Christmas trees dates from only the 14th century and has a less orthodox origin.

Why a tree at Christmas?

It is a legacy of the Pagan festivals of light.

When the shepherds gathered around the crib where, according to legend, Jesus Christ was born, there was not a single fir tree in sight. Pine and fir trees are not really typical of the vegetation of the arid region of what are now known as Israel and Palestine. Therefore, the origin of the tradition of putting up a green tree at home to celebrate Christmas lies elsewhere.

At the time of Europe's conversion to Christianity, the birth of Jesus - whose real date of birth is still unknown - was commemorated at the time when Northern Europe celebrated the Winter solstice, whereas in the South people celebrated the birth of Mithras the Sun-God. These winter festivals celebrated the victory of light over darkness, the Sol Invictus (the undefeated sun). In Northern Europe, the Germans celebrated the victory of life over the death of winter by decorating their homes with evergreen plants such as mistletoe, holly, juniper and ivy. The tradition of making Christmas crowns with their branches comes therefore from the Germans.

The first missionaries, such as Willibrodrus and Boniface tried to end this worshipping of trees, but never totally succeeded. Certain Pagan traditions were adopted by Christians. For example, they hung Lady Chapels on Christmas trees.

Tree celebrations during the winter solstice period reappeared at the time of the Renaissance. The first representation of a Christmas tree was found in Germany, on a painting on parchment dating from the 16th century showing a tree being transported to the village square, escorted by a procession of pipers and a horse-rider, wearing a tiara. It is not known exactly how the tradition of trees with needles developed, but there is one possible practical explanation. At a time when oak trees were becoming rarer, fir trees were very widespread in Germany and it was therefore easier to cut them down and transport them.

At that time, it was already fashionable to decorate trees with Christmas balls. Previously, the balls were late apples which were still hanging on the apple tree and which evoked the earthly paradise.

Christmas trees only really began to gain in popularity in Europe in 1837 when Hélène de Mecklenbourg, the German wife of the Duke of Orleans, had one planted in the Tuileries in Paris. Prince Albert of de Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, married to Queen Victoria of England, was responsible for introducing the Christmas tree into the British Isles.

7. The Magi, who were they?

There is no mention in the Bible of the "three kings" Caspar, Melchior and Balthazar, it refers solely to the "Magi" without any names but a full-blown culture has nonetheless sprung up around the Epiphany.

The processions and mystery plays in the churches commemorated the generous gifts of myrrh, incense and gold. Come 6 January, the nuns and monks would distribute bread to the underprivileged members of the community.

Stefaan Top (Catholic University of Leuven), a professor specialising in folklore, reckons Epiphany songs appeared in our part of the world in the 15th or 16th century. At the time, Christmas could no longer be celebrated with songs and a festive meal in the church. Unable to count on free food and drink, the needy people then thronged the streets out of pure necessity.

For several centuries, the Epiphany was the Feast of poor people. The Magi would go from door to door singing a song, struggling to earn a bite to eat or better still a small sum of money for their trouble. After all, the Magi did shower the infant Jesus with gifts. The begging songs could be performed on the 13th day after Christmas : on 6 January.

These occasional singers would disguise themselves, according to Herman Dewit, a member of the 't Kliekske folk group, who has undertaken research focused on the Epiphany. Some of them even wore a mask.

One of the common features of the carolling kings would be the star they would be twirling to make it revolve. Some even moved about on a rocking horse or a bear. A pot covered with a pig's bladder, known as a rubbed drum, or an instrument cut into clog would be used to accompany the songs. Dewit jokes that the "quality of the music no doubt left a lot to be desired but this was a minor consideration. The groups would make quite a din and the begging singers were mainly intent on attracting attention so as to make as much as money as they could in the shortest time possible".

When this period of gruelling poverty drew to a close, the Epiphany assumed a charitable dimension. Small groups of adults would sing songs to make money for a good cause rather than for themselves. Missions, for example. This custom is still observed nowadays in certain regions, such as Dendre. However, the children have now taken up the torch, or rather the star.

The Epiphany is not only synonymous with going from door to door singing for money. The feast would not be complete without tarts or pancakes. The person who finds the bean or lucky charm hidden in the cake becomes the king and is entitled to wear a paper crown. This tradition also hails back to our ancestors who would rummage through a bag full of wooden statues representing the king and his court.

The roles were then assigned for the big game. The court jester, the king, musician or soldier. The king would have the sovereign right to decide who would play what part. He was the unchallenged and unchallengeable master. If he drank, his companions would have to do likewise. According to Bart, a baker from Ghent, the frangipane sold during the Epiphany originated in the tiny French village of Pithiviers. History has it that after a visit to his friend Madam Marie Touchet, King Charles IV was imprisoned by a gang of Huguenots in the Orléans forest.

When the bandits realised their mistake, they tried to curry favour with the king by offering him a local delicacy. The king enjoyed the puff pastry so much that he bestowed the title of "pastry maker to the king" on the person who invented the recipe. The meat stuffing was then replaced by almond paste.

8. Candlemas, origins and traditions

Candlemas, which first became a Christian festival in 472, is celebrated every year on 2 February. It derives its name from the "candles" or the blessed candles carried during the procession in honour of the presentation of baby Jesus in the temple and the purification of the Blessed Virgin. The pilgrims who flocked to Rome on this occasion led the Pope to organise the distribution of waffles and galettes.

But before becoming a Marian festival (in honour of the Virgin Mary), Candlemas, also called the "Festival of Light", was a pagan festival.

The Romans celebrated, around 5 February, Lupercus, the god of the wilds and fertility.

The Celts celebrated Imbolc on 1st February. This rite, in honour of the goddess Brigid, celebrated purification and fertility at the end of winter. Peasants carried torches through the fields praying the goddess to purify the land before the sowing period.

In the 5th century, Pope Gelasius 1st associated this pagan rite of the "festival of candles" with the presentation of Jesus in the temple and the purification of the Virgin.

From that time on, for this festival which became the "Festival of Light", candles were lit throughout the house and blessed candles were brought into the home to protect it and the upcoming harvestings. The survival of a distant myth relating to the solar wheel apparently also explains the custom of pancakes (or round doughnuts, in the south of France), which are traditionally made at that time of the year.

Various kinds of galettes or pancakes are found in all civilisations of the Old and New World, whether made from wheat flour, rice flour, cornflour or other cereals.

It was in the 12th century that the crusaders brought buckwheat from Asia. The acid soils of Brittany were particularly propitious for the development of this cereal plant.

However, it was not until a century later that buckwheat ground into flour was used for making galettes. At the beginning of the century, wheat (wheat flour) appeared and milk was added to the composition of the mix. The galette became a pancake.

Buckwheat galettes are still today eaten most frequently with savoury fillings while pancakes are served as a dessert.